Manufacturing Industry Outlook: Summer 2022

The following article was first published on the Manufacturing Insights section of RSM’s website. It is reposted here with permission.

Geopolitical shifts, corporate investments to increase resiliency, and various governments’ focus on self-sufficient supply chains are trends that are reshaping global trade.

The need for companies to make their supply chains more resilient is not new; efforts were already underway to address weaknesses highlighted by trade wars and further exacerbated by the pandemic.

But the increasing preference of governments to use trade policies as a political tool continues to influence domestic policies and international partnerships.

These movements are making geopolitical risk a top consideration as manufacturers redraw and rebuild their supply chains by adding more factories, suppliers and material sources.

Geo-Economics

Geo-economics is “the application of power politics by economic means,” as the World Economic Forum puts it, adding: “Countries have been increasingly participating in this form of active economic intervention by applying sanctions, export controls, and subsidies, while developing investment-screening mechanisms and data-localization measures.”

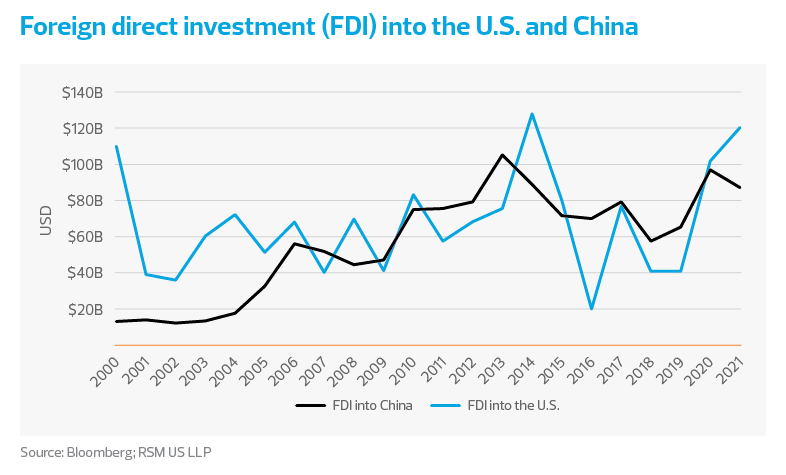

One clear example of geo-economics at play is the adversarial relationship between the U.S. and China, in which both countries have applied various economic measures against each other.

The U.S. is closely reviewing all trade, economic, and financial dealings with China through a national security lens.

The U.S. is closely reviewing all trade, economic and financial dealings with China through a national security lens.

The U.S. Committee on Foreign Investment has heightened its scrutiny of deals involving Chinese investors—this has reduced the number of voluntary investment declarations by Chinese investors.

The Securities and Exchange Commission is moving closer to delisting Chinese companies based on a new rule (specifically targeting Chinese companies) that requires foreign companies to submit an audit that can be reviewed by a U.S. committee.

Chinese and Hong Kong-based companies are subject to their own local government restrictions that make it impossible to comply with the new rule and hence put them at risk of being delisted.

China, too, has introduced new data security and localization rules that impose obligations on multinational companies operating in or conducting transactions with China.

Sanctions

The U.S. government has deployed sanctions and passed legislation that prohibits imports of products made in the Xinjiang region in response to allegations of forced labor issues there.

It is also demanding that the International Finance Corp. (the World Bank’s private sector lending arm) stop funding certain Chinese companies implicated by these allegations.

Recent concerted sanctions by the U.S. and other countries against Russia also emphasize the role of economic tools to achieve political outcomes.

The number of U.S.-sanctioned entities increased from 912 in 2000 to 9,421 in 2021.

The number of U.S.-sanctioned entities increased from 912 in 2000 to 9,421 in 2021, according to the U.S. Treasury 2021 Sanctions Review, issued in October 2021.

As the United States and other countries increase their use of sanctions, companies will hesitate to invest in these economies and may give up investing in economies that don’t align with U.S. ideologies.

The push by Western governments to reduce reliance on China will open new investment and trading opportunities as countries look to rebuild critical supply chains, pursue self-sufficiency through reshoring, and consider “partner-shoring” with their allies—i.e., setting up manufacturing operations in allied countries.

Trading Blocs

Geo-economics is increasingly bifurcating the world and creating trading partnerships based on political ideologies. Trading blocs are not new; we have the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement for the North American economies, and the European Union essentially operates as a single market to its members.

However, with growing geopolitical tensions, polarization appears to be growing between the two major segments of the world economy—the democratically aligned market economies (mostly Western countries, led by the U.S.) and autocratic, state-controlled economies (led by China).

The U.S. government is intent on building international alliances to combat a rising China, one example being its pursuit of an Indo-Pacific economic framework to strengthen its position in Asia. The U.S., United Kingdom, and Australia are entering into strategic partnerships as “like-minded” countries.

The Biden administration has been discussing a “quad” comprising the United States, Australia, Japan, and India to structure supply chains away from China.

Polarization appears to be growing between the two major segments of the world economy.

European countries that have been reliant on oil and gas from Russia are now increasing natural gas imports from the U.S. to reduce their dependence on Russia.

On the other hand, China has entered into a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership with 30 other Asian economies that eases trade among these countries.

China is also applying to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership—a key trade agreement heavily focused on the Pacific countries (and which the U.S. helped broker and later abandoned).

Through economic incursion, China has built its strategic footprint across many countries in Asia, Africa, and even Europe. China and some economies continue to trade with Russia outside the U.S. dollar-denominated financial system.

Geopolitical Risks

Companies will need to be more mindful of geopolitical risks in this bifurcated world. Companies and governments worldwide should reevaluate their supply chain dependencies and review their global portfolios to analyze their manufacturing and assembly footprints.

The tariff wars several years ago and the pandemic had already heightened the importance of such reviews, but manufacturers should continuously assess their operations and strategies in light of these evolving trade partnerships and their implications.

“The anti-Russia bloc—which collectively accounts for 58% of the global GDP—can now use their renewed ties to foster new opportunities for economic growth,” wrote Bloomberg analyst Bryce Baschuk.

“Whether it is through defense spending, energy investments or standards setting, policymakers may develop a ’common market among democracies’ and ’create a relatively even playing field among allies that can foster healthy competition.’”

Companies with global supply chains need to factor the risk of relying on politically unstable or undependable economies.

Companies with global supply chains need to factor in the risk of relying on specific economies that are politically unstable, undependable, or may be subject to sanctions.

Trade and politics are more intertwined today than ever before. China is a significant market, and pulling out may not be an option. To protect against downside risk and balance the geopolitical risk of investing in China, middle market companies can increase their investments in the U.S. or its allies.

In Kearney’s Reshoring Index, 90% of manufacturing executives/CEOs—of predominantly middle market companies—reported having a reshoring or nearshoring target for the near future.

As more American companies move ahead on reshoring and invest in automation, this will encourage other companies to do so as well. Supply chains will need to be more localized and regionalized to counter any risks from broader global conflicts.

About the author: Shruti Gupta is an industrials senior analyst in RSM’s Industry Eminence Program, which positions its analysts to understand, forecast, and communicate economic, business, and technology trends shaping the industries RSM serves.

RELATED

EXPLORE BY CATEGORY

Stay Connected with CBIA News Digests

The latest news and information delivered directly to your inbox.