Latest Population Data Reveals New Headwinds

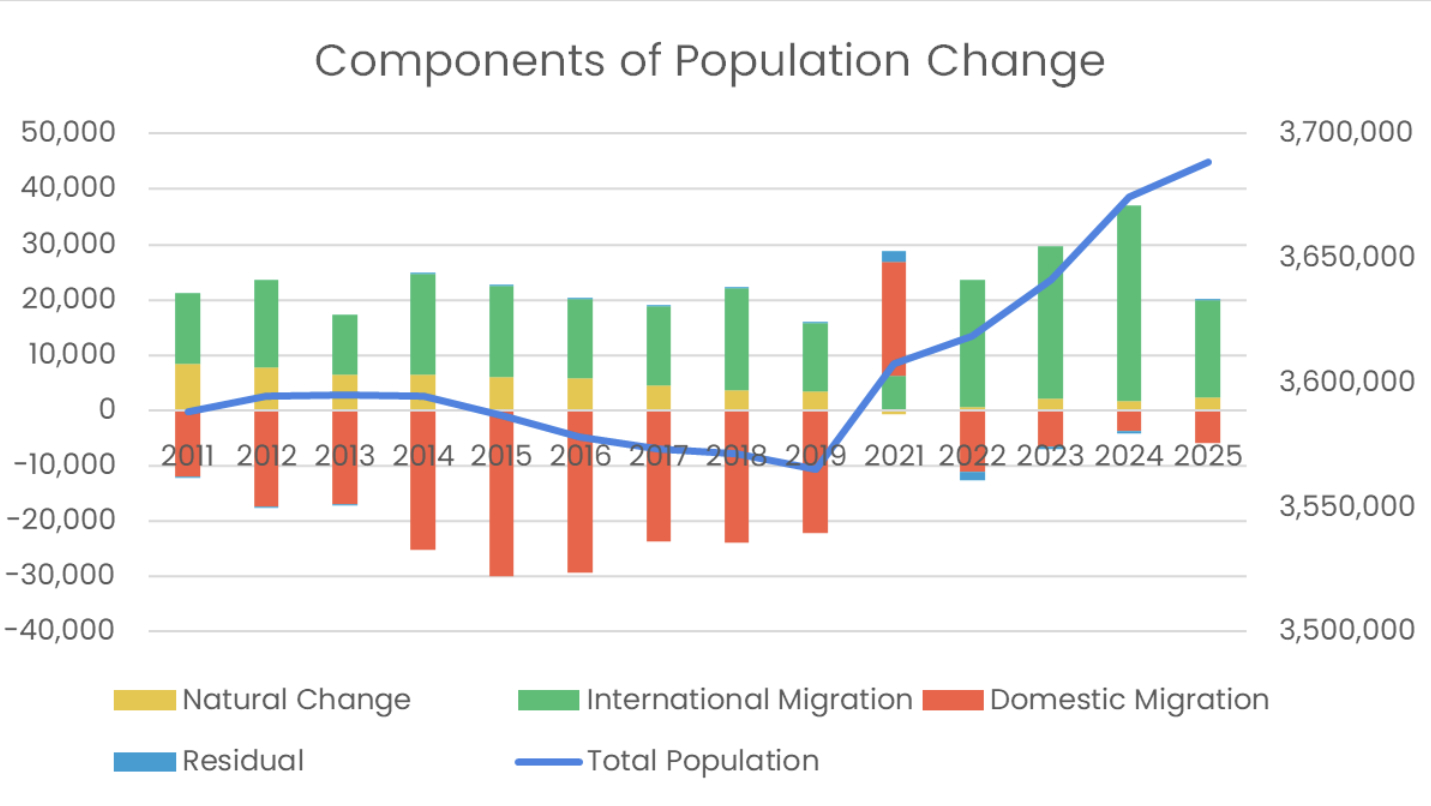

Connecticut’s labor force has barely grown in 15 years. The state’s recent population growth—fueled by a surge in international migration—had offered a rare bright spot.

But last week’s U.S. Census Bureau estimates revealed that bright spot took a major hit, with international migration falling by half in 2025, dropping from 35,456 in 2024 to 17,534 last year (-51%).

To understand why this matters, we can go back to before the pandemic and look at where Connecticut was.

During the 2010s, the state was losing an average of 22,000 residents per year to other states, with 103,152 residents leaving from 2015 to 2019 alone.

Meanwhile, Connecticut offset some of losses through strong international migration, averaging about 15,000 new international migrants annually.

Despite this, the population shrank by about 14,000 people over the course of the decade.

International Migration

As many have felt by now, the pandemic reversed much of that trend. International migration surged to a peak of 35,456 in 2024 and averaged 28,661 per year between 2021 and 2024.

At the same time, domestic migration patterns reversed briefly, with 20,664 people moving to Connecticut from other states in 2021.

That figure settled at an average outflow of 7,143 between 2022 and 2024, a negative but much improved situation from the prior decade.

What’s clear however, is that despite improved domestic migration figures, Connecticut still heavily relies on international migration to grow its population.

Without sustained, strong international migration, the state’s population would have been stagnant or declined in the post-pandemic period.

A Limit on Economic Growth

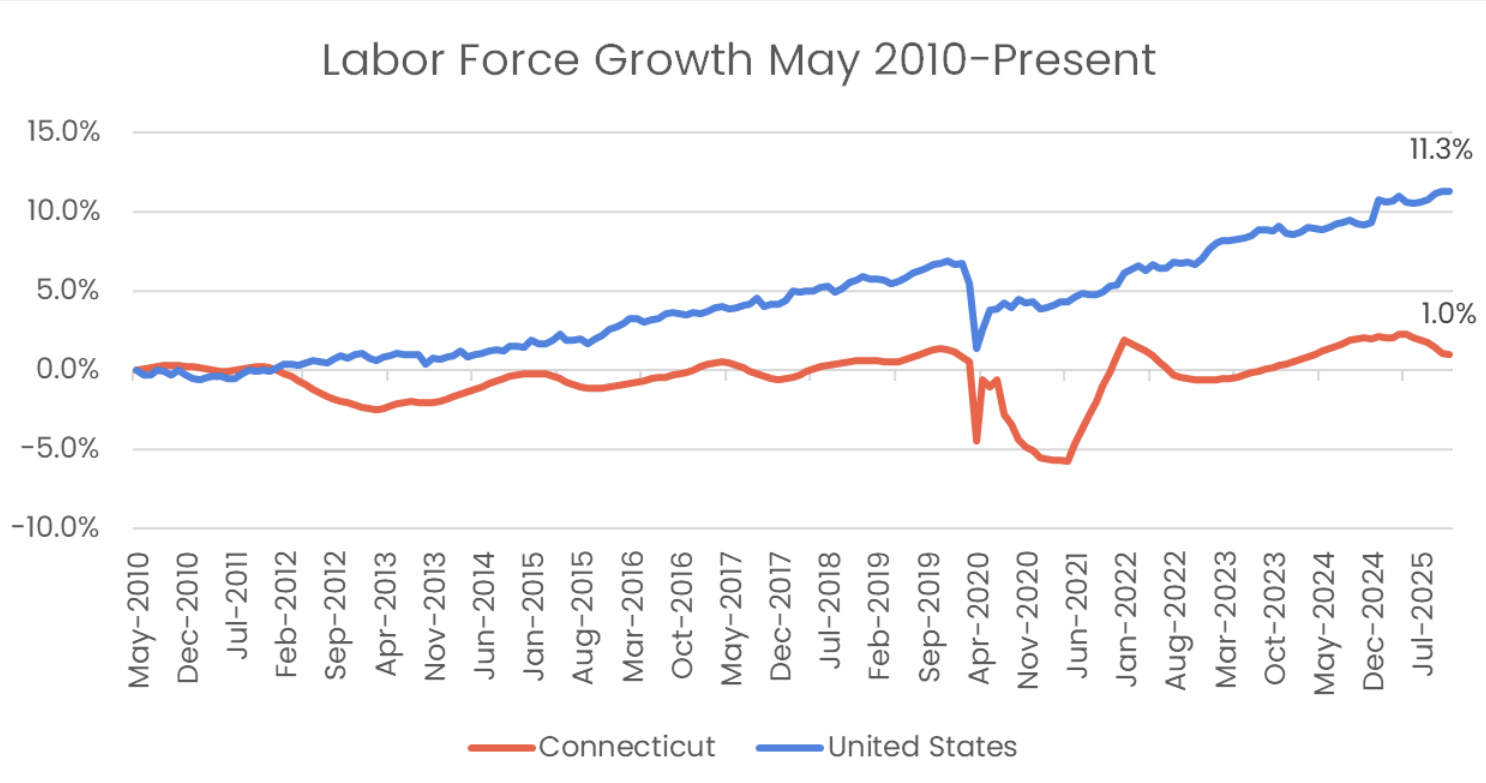

Yet even with population growth, the labor force—those working plus those actively looking for work—has struggled to keep pace with the nation.

Connecticut’s civilian labor force sat at roughly 1.92 million in May 2010. By May 2025, it peaked at just 1.96 million—a gain of about 43,400 workers over 15 years. That’s roughly 2.3% growth, far below the national pace of 10.6%.

December employment data shows that since the peak, Connecticut’s labor force declined by 24,500 people, erasing more than half of the gains from the previous decade and a half.

The lack of growth in the labor force over that period is in part due to the change in labor force participation.

From May 2010 to December 2025, the labor force participation rate dropped from 68.3% to 64%, while nationally that figure dropped from 64.9% to 62.4%.

This disparity is at least partially due to the age composition of the Connecticut workforce, which is the second oldest in the country. Our inability to adequately replace that population means we have not been able to grow the workforce overall.

It is not for lack of demand from employers either. While job openings have come down from their peak, they still stand at 74,000 in November. That is compared to monthly average of 52,000 during the 2010s.

Reversing the Trend

Recent population data clearly demonstrates that Connecticut cannot rely on any single source of population growth to meet its workforce needs.

Federal immigration policy is outside the state’s control, and the 2025 estimates show just how quickly that pipeline can narrow.

Even these estimates are only through July of 2025, and it remains to be seen what current administration policies mean for immigration going forward.

Domestic migration, while improved, remains negative. And natural change—births minus deaths—contributed just 2,283 people in 2025, with the difference between births and deaths continuing to narrow over time.

Connecticut cannot rely on any single source of population growth to meet its workforce needs.

What the state can control are the factors that determine whether people want to live, work, and stay in Connecticut.

That means tackling the cost of housing, which constrains the state’s ability to absorb new residents regardless of where they come from.

It means ensuring the business climate supports job creation and that employers can find the workers they need.

And it means building a workforce development system that can do more with a tighter pipeline—connecting existing residents to opportunity, upskilling workers already here, and removing barriers to participation for those on the sidelines.

About the author: Dustin Nord is the director of the CBIA Foundation for Economic Growth & Opportunity.

RELATED

EXPLORE BY CATEGORY

Stay Connected with CBIA News Digests

The latest news and information delivered directly to your inbox.